May, 2024 Megillah

RABBI'S NOTES

Back in deepest February we celebrated Tu B’Shevat. We blessed and drank four cups of wine, the first white, the second pale pink, the third half-and-half, and the fourth full deep red. As we drank we blessed and ate fruits with different characteristics: from a hard shell to a central pit to edible all the way through. All of this was to invite us to ascend the Tree of Life, from the material plane (not much color, hard peels—the kabbalists who thought up this practice may not have held the material world in high esteem) through the world of formation to the world of desire for existence up to the ineffable, indescribable plane of the Divine Mystery.

At the end of our Caspar Tu B’Shevat seders, after that spiritual ascent, we have always paid some lip service to returning to the earthly plane. So it didn’t occur to me until this Pesach that perhaps the descent isn’t meant to happen then, but months later. Maybe we stay in that ascended place until we begin counting the Omer. Maybe, in the language of the growing cycle, we begin our ascent when the ground is just barely unfreezing. We stay in that cosmic place through the planting, until the crops begin to sprout. Then we begin to descend until the barley back here in the garden is bearing fruit.

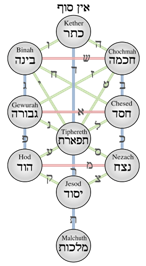

The kabbalistic language is slightly different, but the practice of counting the Omer transports us, as it were, from the top of the Tree of Life back down to the bottom. We start (today as I am writing, which happens to be the second day of Pesach) in the world of chesed—lovingkindness, flowing compassion—and we will work our way down the Tree over the next seven weeks to the world of malchut, regular daily life.

If you’re not so dialed in to this kabbalistic language of ascent and descent, olamot and sefirot, this may sound a little esoteric at best. And it is! My first exposure to any kabbalah came decades ago in our Tuesday morning reading group. We decided, without quite knowing what we were getting into, to read Sefer ha-Bahir, an early kabbalistic text. (Like many kabbalistic sources, it said of itself that it was written in the first century CE, though more critical scholars say it was composed in the thirteenth century.)

It is composed of 200 short passages amounting to 82 pages in the English version we used. We took two years to read it aloud to each other and mull over the paragraph or two we had just read.

At the end of the two years, I remember saying that I didn’t understand a single word of what we had read and discussed, but I felt like all my cells had changed.

I attended a seder last night in which people at the table were talking about “what’s going on in the world.” And as I listened I began to question that very phrase: “what’s going on.” What IS going on in the world? I’m still no kabbalist, but I am drawn to the language of ascending and descending the Tree. I love it for a number of reasons. One is that it helps me perceive the world as layered. It is tempting, especially in this era of never-ending (usually bad) news, to think of “the world” as being all news. Or news plus our personal networks of friends and family with their own news cycles.

To see the world as tree-like is to see it having roots below the level that we can perceive and to see it ascending up above our reach to the sky. It’s not so hard to picture the tree breathing, metabolizing, blossoming, fruiting, dropping leaves. Practices that invite us to ascend and descend, as it were, suggest there are aspects of life which are spiritual: cyclical, connected, generative, nourishing, beautiful, and not easy to comprehend or control completely. All of this is part of “what’s going on.”

Practices of ascent and descent—like the mirror-image practices of Tu B’Shevat and counting the Omer—invite us to reach up into that spiritual realm and bring it, as it were, into our material lives. I think we need that capacity now as much as ever. As some of you know, because I’ve been belaboring it over the past months, I am thinking a lot about how we can build our resilience, to use a term of the moment, so that we can meet whatever the future brings our way in as whole a way as possible. One piece of that resiliency, I think, may be to be able to ascend and descend through layers of world.

Some of us are very comfortable in spiritual realms. Others of us may not settle in so easily. For still others it may seem ridiculous to even consider that there are realms or worlds beyond the material. I sat quietly here for awhile between this last sentence and whatever I am going to write next. I wanted to say, “If you are one of those people for whom this kind of ascent doesn’t come naturally, try this.” Much of Jewish practice is a treasure box full of methods for cultivating our spiritual capacities.

But on a little more thought, I had another idea. We are in life together. Maybe it is more existentially efficient when some are practical and material-minded and others are tuned into spiritual dimensions.

Maybe at any moment one of us is breathing in the highest, deepest level of Divine inspiration, while another of us is figuring out how to fix the roof or end war. Maybe some of us function in a more natural and intact way in one plane or another. Or maybe we can all strengthen our capacities to ascend and descend, to move “upward” (all this being so very metaphorical) into more spiritual ways of being and feeling and “downward” into addressing material issues with wisdom and grace.

To lean into this metaphor still further, maybe the skill we all need to nurture is to be able to hold and transport the juice from one level of reality into another; in the language of counting the Omer, to draw down the characteristics of the upper realms into the lower. With the method of counting the Omer which comes from Lurianic Kabbalah, we get a lot of practice. We draw down from the world of chesed day by day and week by week. Lots of drawing down.

What might it mean to draw down from the world of chesed or any of the upper realms? it might mean to try to be more loving and more compassionate, a good idea any day of the year. But it might also mean remembering that “what’s going on in the world” includes a layer of love, compassion, grace, generosity—always present, always part of what is. Hard to feel sometimes, hard to trust, but always worth exploring. Likewise, with the next sefira (gevurah / strength, boundaries, containment). This energy is always present as well, always possible to access. And so on down the Tree: tiferet / beauty and balance, netzach / power, expansion, hod / humility, gratitude, yesod / form, intention, and malchut / the good old material plane. All of this is what’s going on. All of this is operative at the same time. We can draw from these layers of God-ness, of meaning, of reality to meet the challenges of the moment.

At the seder we make a “Hillel sandwich” of matzah, horseradish and charoset. It’s the last ritual act of the first half of the seder. Then we eat dinner. I’ve always loved the weird combo of flavors. But I never really got the sandwich aspect until this year. Life is not just the bread of affliction, not just bitter herb, not just sweet apples. It’s about the layers.

First we sit with each one separately, and then we bring them together. We remember that each moment has all of it: sweet, bitter, crunchy. Life is a Hillel sandwich. The Omer is a fancier sandwich, with seven layers instead of three. That’s what’s going on in the world. May it come to us and to all for good.

PAIGE NOTES

Writing for publication is inherently a form of time travel. We write knowing that it will not be read until a new month, when stars have shifted, not yet known world events have happened, and we’re all in different places than we are in this very moment. This feels present for me every month as I write my Megillah entry, trying to channel the energy of the next Hebrew month, though I still feel very grounded in the current one. This reminds me of the notion from the Torah that אנחנו לא־נדע מה־נעבד את־יהוה עד־באנו שמה “We do not know how we will serve the Divine until we arrive there” (Shemot/Exodus 10:26).

I write this on the first day of Pesach when Moshe utters this profound observation to Pharaoh right before the Tenth Plague. We often know what we intend to do, but not how we will do it.

Alternatively, we often know what we are doing, yet not where it will lead. The mystery proves to be a crucial part of our mystical journey, emphasizing the etymological root of myst (“secret” in Greek). “We do not know how we will serve the Divine until we arrive there.”

As we approach the new moon of the Hebrew month Iyar, we spend all of Iyar, as well as the end of Nissan and the beginning of Sivan, Counting the Omer. We have a theme for each of the 49 days to guide us on this journey. We stand on the shoulders of giants, knowing that our counting will last exactly seven weeks and lead us to Revelation, receiving the Torah on Mount Sinai on Shavuot. More often in life, though, we do not know how many days we’ll be counting; we have no idea how long it will take to get to where we’re trying to go. That uncertainty can feel unsettling, especially if we don’t even really know where we’re going. One of the lessons of life seems to be learning how to cultivate settledness in that uncertainty. It’s not yet Iyar, I’m just time traveling here, but maybe that’s what Iyar will be all about: how to trust that we will indeed serve the Divine, even if we do not yet know how.